Green Giants

Green Giants: Mega-producers tip scales as organic goes mainstream

Carol Ness, Chronicle Staff Writer

That's one big bowl of salad -- way bigger than when

This is the yin of the organic food movement as it plunges headlong into the American mainstream.

The yang is County Line Harvest farmer David Retsky, steering an orange tractor to sow organic Palla Rosa radicchio, Easter Egg radishes and Cosmic Purple carrots on the 6 hilly acres he farms outside

Both farms are certified organic. But they couldn't be more different in scale, in how far their produce travels, in how much fuel is burned to produce and deliver it, in how fresh it is when it gets to market, and in how much it costs.

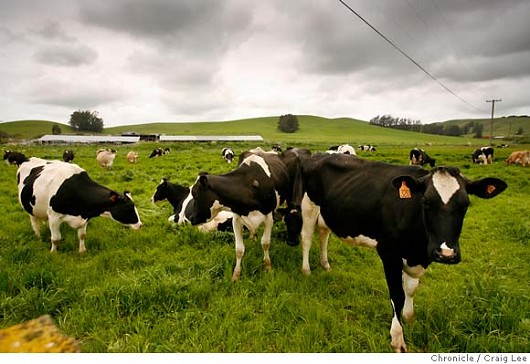

Consumers who think they're buying from a small local farm may actually be buying from a company moving up to half-a-million pounds of lettuce a day. Their organic milk might come from cows grazing on lush spring grass near

Organic convenience foods and snacks might be manufactured by

"I think organic is not quite what people think at this point," said Michael Pollan, a UC Berkeley journalism professor whose new book, "The Omnivore's Dilemma," takes a hard -- and ultimately critical -- look at what he calls "industrial organic."

Whether it's salad -- or milk, or eggs, or cookies -- these kinds of differences come into play up and down the organic food chain. And with stores like Safeway and now Wal-Mart packing their shelves with organic products, which style consumers buy -- the yin or the yang -- may determine what organic will look like in the future.

The differences don't mean the food isn't organic. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's green organic seal means that it's certified -- that it was grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides and processed without forbidden chemicals.

However, critics of large-scale organics say that while mega-producers follow the letter of the law, not all follow its spirit. They worry that the movement is sacrificing its soul, that it's strayed from its original ideals of creating a new food system that helps small farms, connects consumers with producers, and cleans up the environment.

Still, the fact that there's simply more organic food around is a good thing, according to people like organic pioneer Bob Scowcroft, executive director of the Organic Farming Research Foundation in Santa Cruz.

"It's something our own movement hasn't been able to do for 30 years -- bring organic to all economic levels," said Scowcroft, who has been there from the beginning, advocates for small farms, and is an activist in keeping the organic food industry at a high standard.

What's brought things to this point is the spectacular growth of organic food, especially in the past two years.

Sales are expected to hit an estimated $15 billion this year, according to the Organic Trade Association, an industry group. That's still only about 2 percent of the

The biggest food manufacturers have scarfed up some of the best-known organic brands and started their own line extensions. Coca-Cola owns Odwalla. General Mills boasts Muir Glen and Cascadian Farm. Smuckers bought out Knudsen and Santa Cruz Organic.

Whole Foods is up to 175 stores, and more conventional supermarkets are getting into the act, too. Safeway has just come out with its O Organics line of cereals, salad dressings and other staples priced barely above its nonorganics.

Independent companies such as Santa Rosa-based Amy's, which makes soups and frozen meals, are mushrooming, too. At Amy's, sales have risen about 30 percent a year for the past two years, and the company plans to open a second plant in

All of this means more organic foods in more markets and lower prices.

"It feels like the tipping point -- like organic's time has really come," said Earthbound's Myra Goodman.

Every day at Earthbound Farm's big, white, refrigerated plant, semis pull in with tons of romaine and radicchio, mache and arugula, some from as far away as

And the numbers are going up. Earthbound just bought Pride of San Juan, its competitor down the road in San Juan Bautista (

To help offset the environmental effects of all those trucks coming and going, the company has planted 400,000 trees to consume all the extra carbon monoxide. And they track how many tons of chemical fertilizers (4,200) and pesticides (135) their operation keeps out of the environment every year.

"We're feeling good about what we do," Goodman said. "We're competing with Dole, Fresh Express and Sunkist, not farmers' markets. Our mission is to give people an organic alternative -- and working to bring it to people where they shop meant we had to get big."

Retsky, at County Line Harvest, doesn't think he's competing with Earthbound. But he's not sure consumers know the difference between what he offers at farmers' markets and what they find at Costco.

He's made an effort, for example, to grow a lot of crops, side by side --

Organic milk is another area where differences in production are profound. Milk produced by smaller Bay Area dairies like Clover Stornetta Farms and Straus Family Creamery has only a few things in common with milk from giant processors like Horizon and supermarket store brands.

On Bob Camozzi's 615-acre Triple C Ranch in the lush

On the other hand, Costco and Safeway house brands, and Horizon, owned by giant Dean Foods, which claims 55 percent of the U.S. organic milk market, buy from many suppliers, including gigantic 3,000- to 5,000-cow dairies in the Central Valley, Idaho or Colorado, where the animals are crowded into feedlots and may never see a blade of fresh grass.

Federal organic rules currently require only "access to pasture," but not actual pasture time. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is considering tightening that rule because of complaints about confinement farms; a public hearing on the issue was held this month in

Consumers care about how the animals are treated, according to a new survey conducted this month by an independent firm for the Center for Food Safety, an advocacy group in

The fight over what is or should be organic has been going on for decades, but the growth of big organics and arrival of powerful players has upped the ante.

Safeway jumped in big-time this year with its O Organics line -- 160 products so far with plans for another 50 by the end of the year. They're identified by the pretty cornflower blue O on the label, without the name Safeway anywhere in sight.

On many items, prices are much lower than nonorganic competitors'. A 15-ounce box of O Organics frosted flakes, for example, is $2.99 at the Fourth and King store in

"There's a large part of the population that sees pricing as a hurdle to organic products, and we wanted to make this available to a larger consumer base," said Safeway vice president Doug Palmer. "Because of Safeway's size, it allows us to be more competitively priced."

Big food companies need to buy huge supplies of organic ingredients as cheaply as possible -- which some observers believe may mean going overseas. "If we want to support organic agriculture in

Already, 10 percent of the organic food sold in the

Yet, some companies go out of their way to buy ingredients from local farmers. Amy's, which has been making frozen meals and soups since 1988, is one.

"Buying locally has been a natural consequence of being in the West. Organics grew up here," said owner Andy Berliner.

Amy's is now sucking up 150 truckloads of onions a year, up from five or six in the mid-1990s, according to its farm liaison, Tom Mello. It uses 20 different onion growers, big and small.

"We feel the backbone of the industry is the small family farm, and we feel indebted and responsible for keeping the small farms alive," Mello said.

The center aisles of the supermarket, the domain of cereals, soups, cookies and chips, is a hot spot of organic action. And processed foods raise a new set of questions.

Nutrition is one. Organic means healthy to many people, but Marion Nestle, a

"Just because these products are organic does not necessarily mean that they are the healthiest options," Nestle said.

Earthbound's Goodman, the mother of two teenagers, has a different take.

"If my kids are going to have a choice of a conventional Oreo with trans fats or a Whole Foods or Newman's organic Oreo without it -- I'm thrilled. I don't have to worry about what's in it and how it's produced," Goodman said.

Consumers are left trying to figure out which kind of organic they want to support with their food dollars.

And that can be tough. Supermarkets don't like to say who makes their store brands. Manufacturers have resisted efforts to have labels say where ingredients come from. And marketing creates illusions that everything organic comes from the picture-perfect small farm.

Another wrinkle is that some organic certifiers interpret the federal rules more loosely than others, causing conflicts that end up in court or in Congress. Growing corporate stakes have meant more big-money pressure on the USDA and on Congress.

The complications have pushed some farmers, such as Rick and Kristie Knoll of Knoll Farms in

The notion of eating locally produced foods, too, is gaining momentum as a fuel-saving, community-building alternative, or addition, to organic.

The idea is building up steam. This month, more than 700 people answered a challenge from a

Ultimately, "What's important is knowing what you're buying," said Russell Moore, a chef at Chez Panisse, where organic/local/sustainable is the mantra. One of the best things about the surge in organics, he said, is that it makes people think about where and how their food is produced.

"Everyone," he said, "has to make their own decisions. I think wherever you are, you can do something that helps."

E-mail Carol Ness at cness@sfchronicle.com.